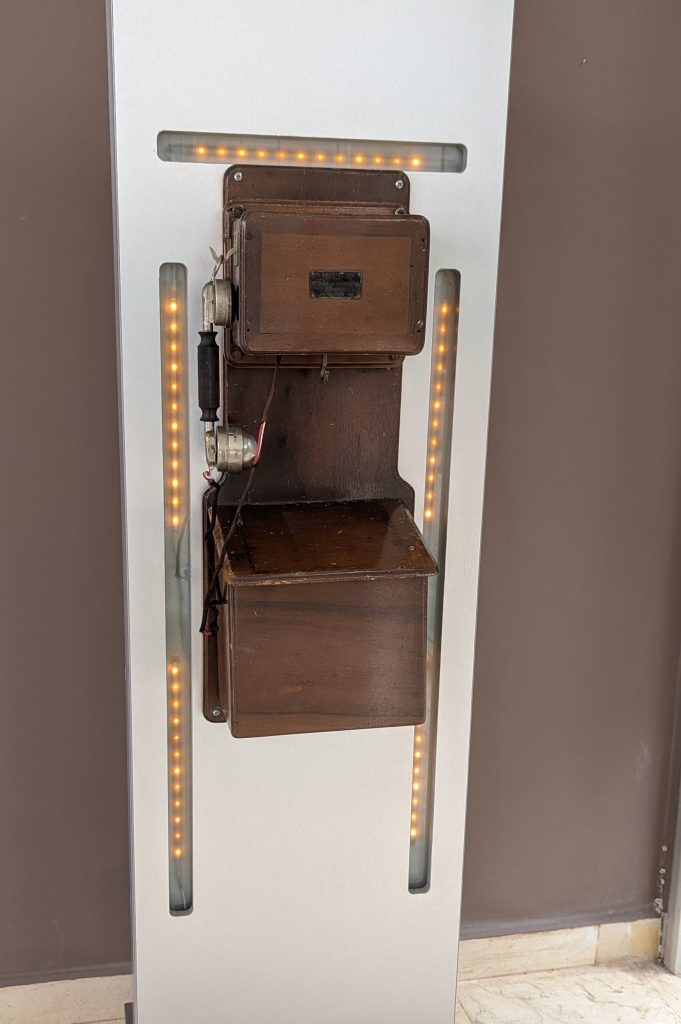

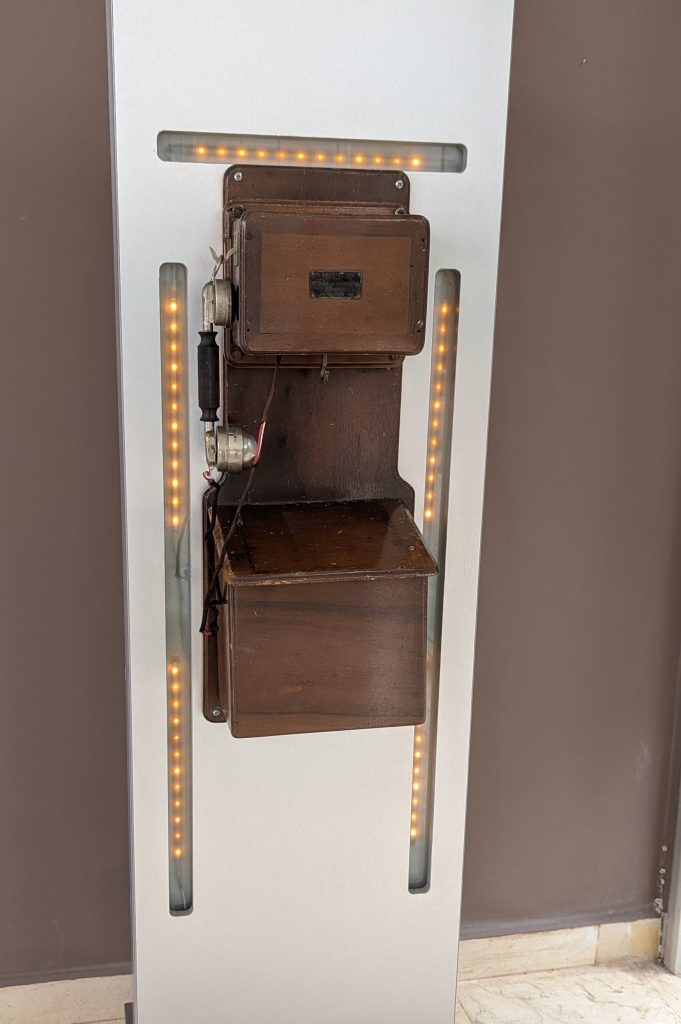

On our recent trip to Marrakesh we came across this small museum in the Medina. It’s near a nice park and worth a visit.

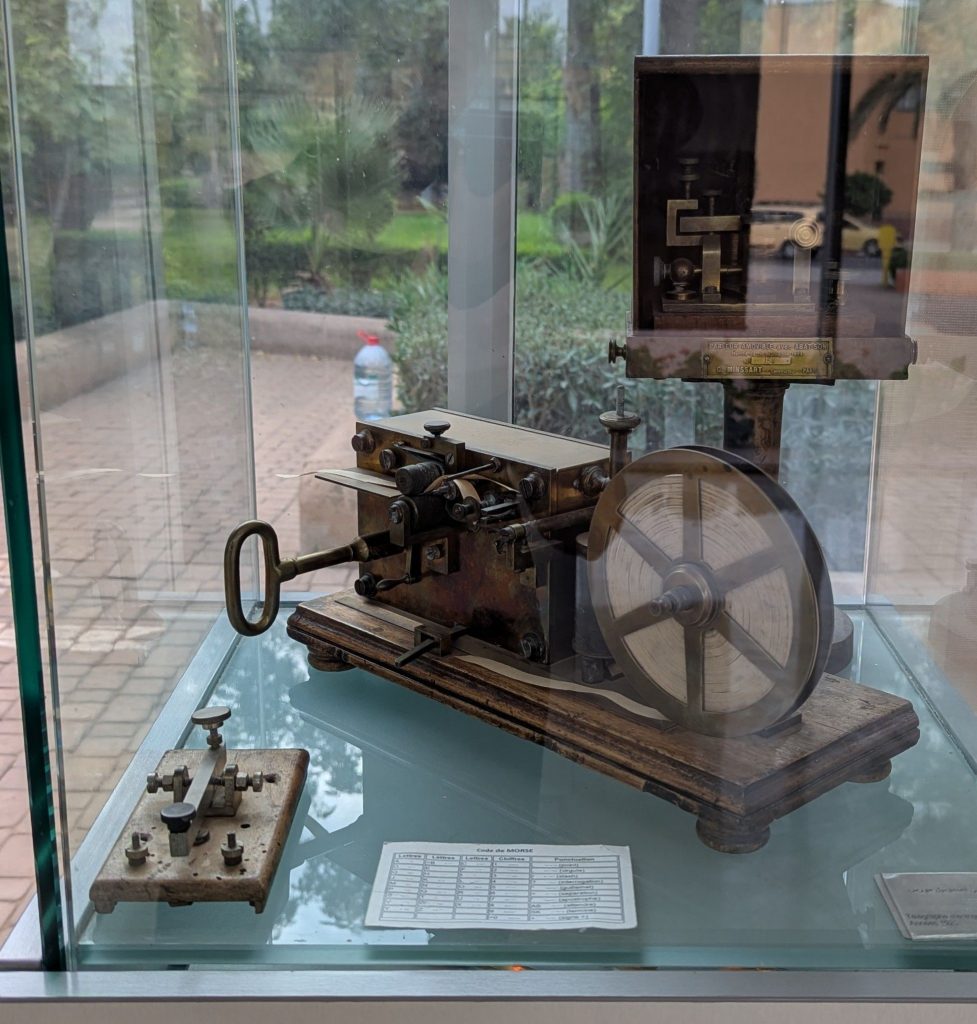

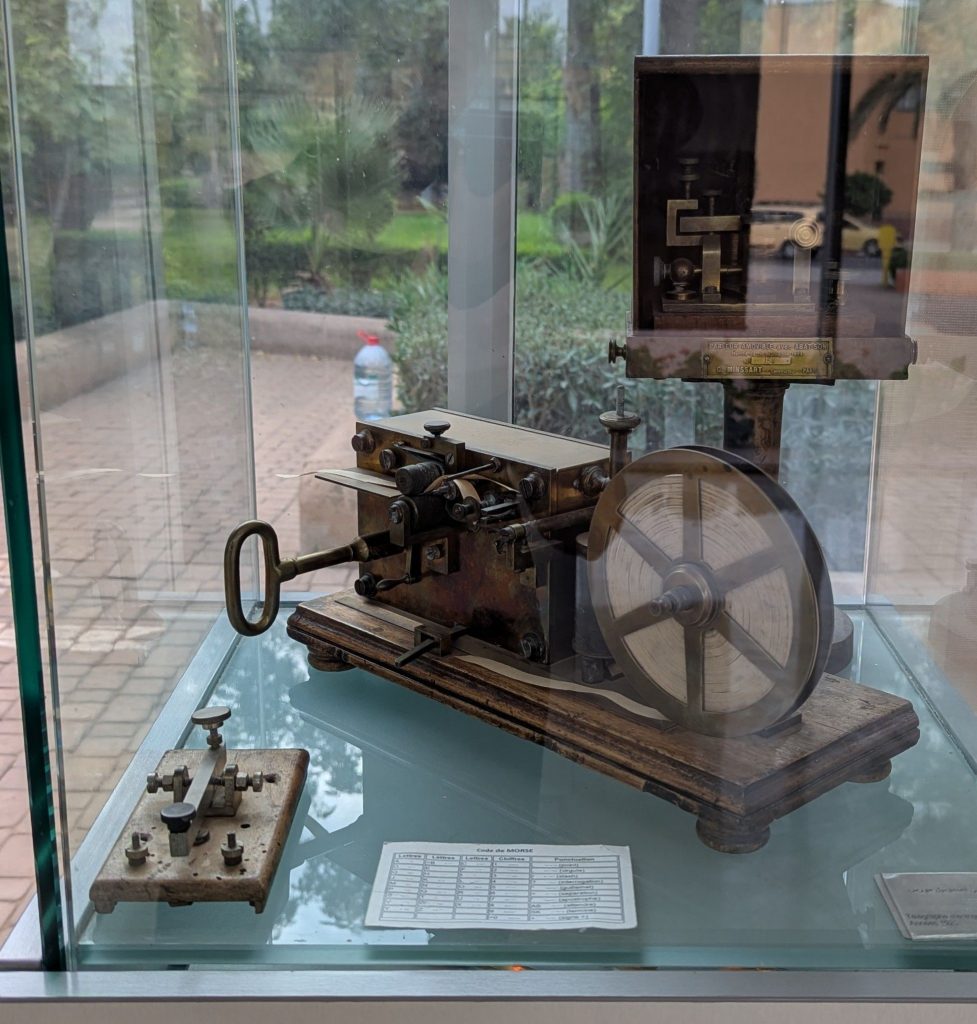

Apopogises for the glare in the photos – there was a lot of glass about.

Not in the museum but in the Medina…

On our recent trip to Marrakesh we came across this small museum in the Medina. It’s near a nice park and worth a visit.

Apopogises for the glare in the photos – there was a lot of glass about.

Not in the museum but in the Medina…

Comments Off on Marrakesh Telecoms Museum

Posted in Geography

Tagged heritage and history, Morocco, urban

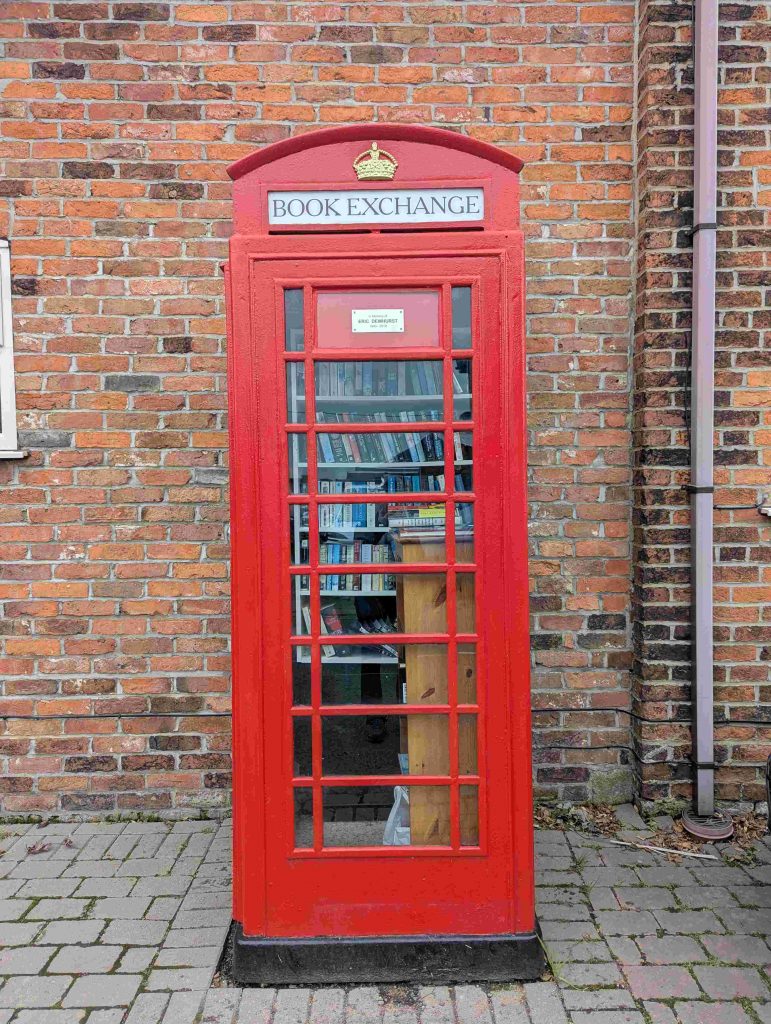

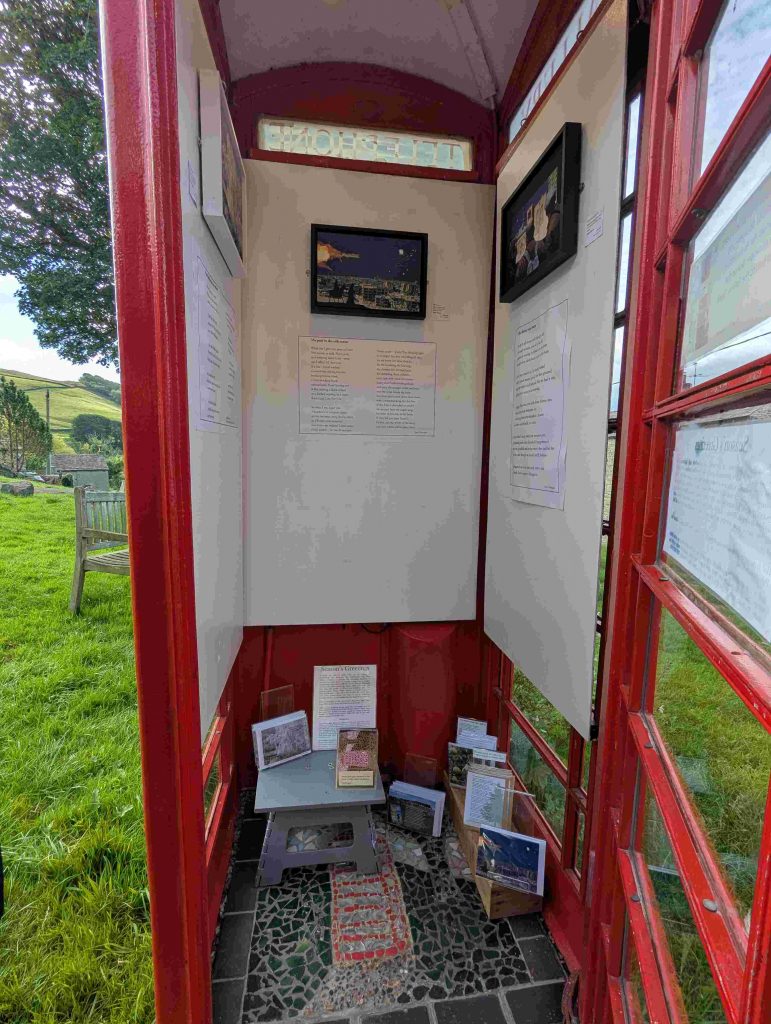

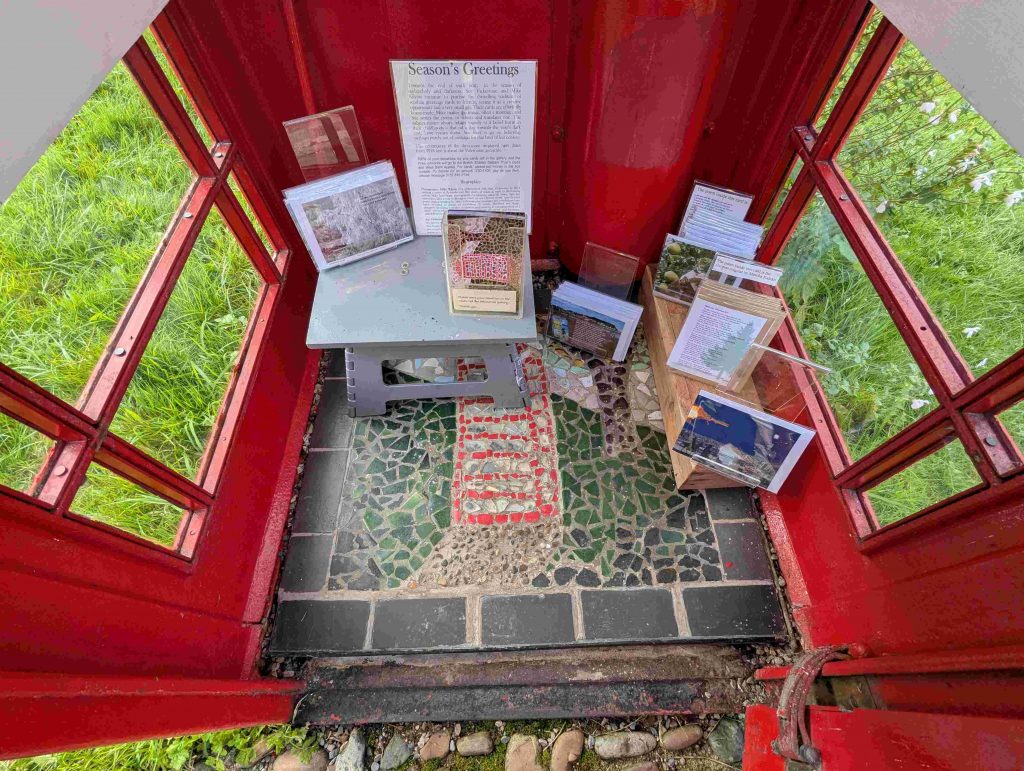

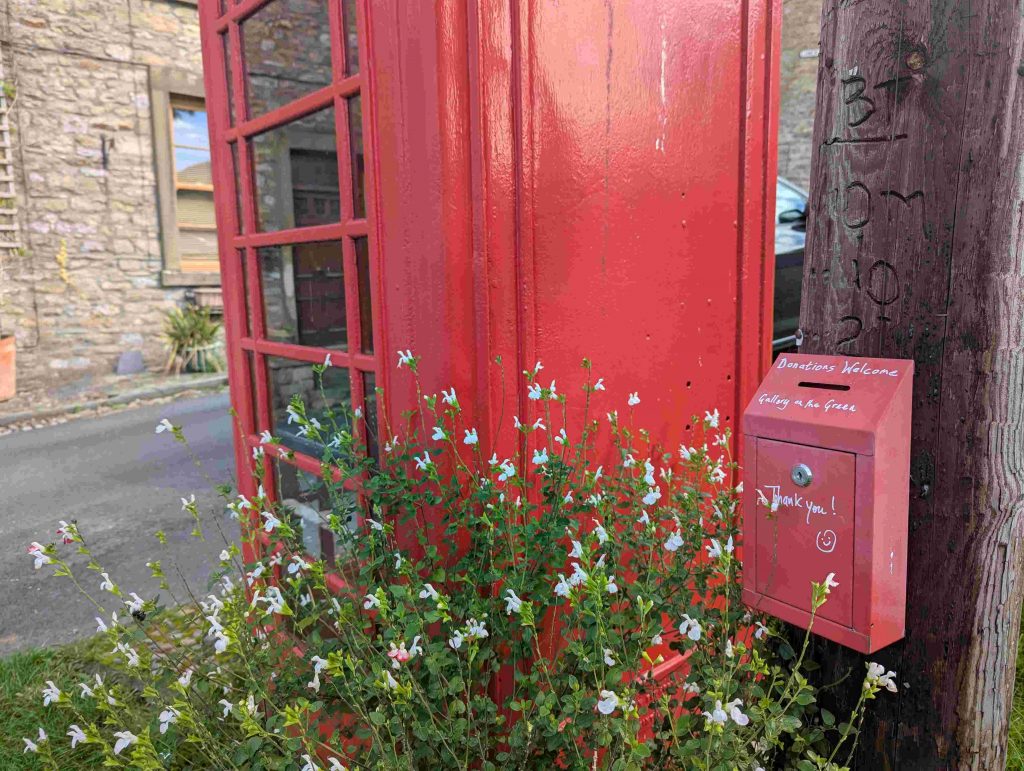

We had a few days in the Yorkshire Dales recently and I was happy to see that the phone box is still very much a part of the landscape.

Here are a few from the Dales in general…

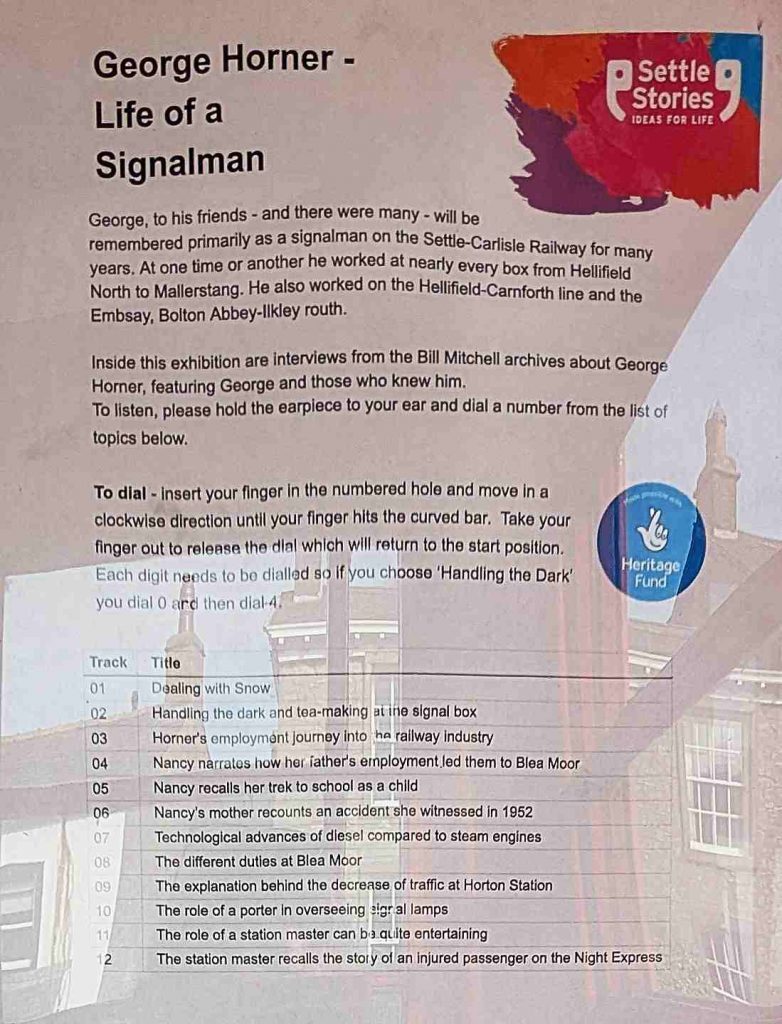

Settle in particular was an excellent find – a mini art gallery and the only speaking phone I’m aware of. The voice of George Horner, a Signalman for many years on the Settle-Carlisle Railway, can be heard by dialing the phone. His oral history stories are part of the Bill Mitchell archive and cover a variety of topics such as dealing with snow and tea-making at the signal box. Apologises for the glare on some of the photos.

An update: I found the image below in the Science Museum files. It appears to be an AA telephone handset. Perhaps it was installed inside boxes such as the Aysgarth one shown above?

Reprinted from The Guardian 24 March 2025.

BT had planned to remove the familiar red kiosk in rural Norfolk until 89-year-old Derek Harris intervened.

An 89-year-old man has won his battle to save the last remaining phone box in a village in East Anglia.

Derek Harris learned in January that BT was planning to remove the K6-style box in Sharrington, Norfolk, where he has lived for 50 years. Harris and his fellow campaigners argued it was “an iconic heritage asset” and a vital asset to the community, due to the poor mobile signal in the rural area and North Norfolk having the highest proportion of older residents in England and Wales.

On Monday, BT informed Harris it had decided not to withdraw the payphone. In a letter, the company said: “Given the poor mobile service in the area and the significant number of calls made from this payphone, it is clear that it serves an important function for the community. Therefore, we are withdrawing it from the removal programme. “We understand the importance of maintaining reliable communication options, especially in areas where mobile service is lacking. The payphone has proven to be a vital resource for residents, ensuring that they have access to emergency services and can stay connected.

“Our decision reflects our commitment to supporting the community’s needs and ensuring that essential services remain accessible.” Harris was born in 1935, the same year that the K6 style of red phone box was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. It went into production in 1936, becoming a familiar sight across the UK in just a few years. Linda Jennings, from Brinton and Sharrington parish council, said: “It’s fantastic, the ‘normal man’ has won over the big company. We are all very pleased. It’s really good that BT has backed down.

“The mobile phone signal is really poor, it’s a lifeline for people. If you can’t get a signal there, you need these phone boxes. We have a parish council meeting on Thursday, Derek will get a big pat on the back.” Last month, Harris told the Guardian of the need for the phone box to remain. “We live next to perhaps the most beautiful part of Norfolk, the tranquil Glaven Valley with a pure chalk stream running through it,” he said. “It attracts ramblers, walkers, the lot, and everyone knows that there’s a working kiosk.”

In the event of an emergency and the mobile network being down, he added, “Wouldn’t it be awful if someone said: ‘If only they had kept that working kiosk’? ‘What you have to bear in mind is the few calls that have been made have been vital, they’ve probably saved someone’s life. Not that long ago, there was a snowstorm.” On that occasion, the mobile network was down and the call someone made from the phone box “was the only way that rescue came to save this driver whose car was completely covered in snow – it fell off the top of the hedgerows on to his car, and he was trapped.”

‘I don’t want it to die’: one man’s battle to save the last phone box in his village‘

Reprinted from The Guardian 27 February 2025 by Emine Saner.

In 1935, Derek Harris was born – and so was the K6 red phone box. Now, Harris is spending his 90th year ensuring this beloved local facility isn’t lost.

The battleground at the heart of a struggle between an 89-year-old man and a multi-billion pound multinational is a small junction in a Norfolk village, where a red phone box stands. And at the red phone box, sheltering from the wind, is Derek Harris. Last month, he learned that BT (formerly British Telecom) was threatening to close the phone box in the village of Sharrington, where he has lived for 50 years, when he saw it on the agenda of the parish council meeting. “I thought: ‘I’d better do something about this,’” says Harris.

He has described it as a “David and Goliath” campaign. It is that, and – as becomes clear on this sunlit but biting February day – so much more. We will talk mortality and reprieves, heritage and value. I’ll leave with a renewed sense of how it’s possible to feel real affection for an inanimate object, and why having a mission matters.

First, though, some field mice. Sharrington is in a picturesque part of East Anglian countryside. “We’re surrounded by open, rolling, wonderful fields – arable, beautiful,” says Harris, “except they’re inhabited by field mice – and field mice have developed a penchant for the PVC that protects the copper cabling [of phone lines]. Opposite the church, which is just up the road, there is a telegraph pole, and in it, there are three mice nesting.” His eyes sparkle. The rodents gnawed through the wires, disrupting villagers’ phone lines and internet. He knows about the mice, he says, because an engineer from Openreach, the BT-owned company that looks after the network, told him.

Harris keeps an eye on Openreach, because there is a green junction box, connected to the new fibreoptic cables, barely a couple of metres from the phone box. It wouldn’t take much to connect the payphone to fibreoptic, insists Harris – as with the whole telephone network, phone boxes will need to be upgraded to digital lines by the time the analogue network is switched off in 2027. “There’s no reason why it shouldn’t be connected, and so I’ve set my heart on it.” He says engineers visit most weeks anyway. “So maintenance [of the phone box] would be no problem. It’s cost-effective.”

The UK has 14,000 working phone boxes, down from 20,000 three years ago; at their peak in the 1990s, there were 100,000. Of these, around 3,000 are the iconic red design. When about 95% of households have a mobile phone, it’s perhaps a wonder that phone boxes survive at all.

Owned and run by BT, and costing millions of pounds each year, they are required by the regulator Ofcom under the quaintly named telephony universal service obligation. In the year to May 2020, almost 150,000 calls were made to emergency services from phone boxes, as well as 25,000 and 20,000 calls made to Childline and Samaritans, respectively.

“We have a legal responsibility to make sure that phone boxes exist to meet the reasonable needs of citizens in the UK,” says Katie Hanson, senior consumer policy manager at Ofcom, who was part of its review on payphones, with new guidance published in 2022. “Obviously, what ‘reasonable needs’ looks like won’t be the same today as it was before everyone had a mobile phone. The approach we’ve taken is to say that boxes that we think are essential are protected from removal.”

‘It faced death in 2016; it’s still here’ … Harris with councillor Andrew Brown (left). Photograph: Joshua Bright/The Guardian

A phone box cannot be removed if it is the last in an area (more than 400 metres from another phone box), and if one or more of the following conditions apply: if it’s in an area without coverage from all four mobile network providers, or if at least 52 calls have been made from it in the past year, or if it is somewhere with a large number of accidents or suicides (Harris hopes his phone box’s proximity to the A148 is what might save it), or, finally, if there is a high social need – for instance, if it has a number of calls to helplines such as Childline or domestic abuse charities. If a phone box is the last at the site, and none of the other conditions apply, then if BT wants to remove it, it has to start the consultation process with the local authority, which is what has happened in Sharrington.

Last year, fewer than 10 calls were made from Sharrington’s public phone box and it is one of 10 in the North Norfolk district council area earmarked for removal. The village, in a conservation area, has a church dating from the 13th century and a Jacobean manor house. Harris believes the phone box is “an iconic heritage asset” and the local MP, Steff Aquarone, has written to Historic England to try to get it listed. “Working K6 models are rare,” says Harris. The K6 (for Kiosk No 6), topped with its gilded Tudor crown, was designed by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott to mark the silver jubilee of George V in 1935.

Harris has lived in Sharrington for half a century; it’s where he and his late wife brought up two children. The phone box has been there for even longer. Both Harris and the K6 share a birth year – 1935 – which partly explains his affinity for it. He spent his early life in Surrey, near Croydon Airport, enjoying the sight of planes flying overhead.

“Very interesting for a little boy,” he says. “It wasn’t such a good location when war started, because airports were targets.” The family evacuated to the south coast, but that wasn’t much safer – German fighter-bombers would attack the area in “tip and run” raids. When Harris was about eight, he survived one such attack while out playing with his brother. “We saw our friends falling wounded; a few got killed.” Years later, as a young man, Harris joined the army and was injured. “A field surgeon saved my life,” he says, but he was warned that he would need multiple operations in the coming years and not to expect a long life (he is, he reminds me a few times, in his “90th year”).

Sharrington’s phone box has also fought off previous threats to its life. “They made an attempt to decommission it in 2016 and we resisted it successfully,” says Harris. “I’ve faced death before, passed through it. It faced death in 2016; it’s still here. Something tells me that it’s meant to stay.” Harris and those campaigning to keep it, including local councillor Andrew Brown, have been given an extra month to plead their case.

“It can be a lifeline, and it’s a conservation asset,” says Brown, “a valuable communication resource, given the nature of mobile signalling being so poor around here.” The area is rural and isolated, some villagers have virtually no mobile signal, and North Norfolk has the highest proportion of older residents in England and Wales – the adults most likely not to have a mobile phone. And it has one of the highest proportions of second homes in the country. In an emergency, without a mobile signal or working payphone, try knocking on the door of an empty holiday home – one that probably doesn’t even have a landline anyway.

Making their case in 2016, says Harris, “we said it was an animate part of the conservation area. It wasn’t just a museum piece, and people did use it.” But, he acknowledges, “probably more than they do now.”

Many of the village elders, who relied on the phone box because they didn’t have mobile phones, have since died, but some elderly people still use it, insists Harris. If the box survives, one of the handful of calls it will have logged in 2025 will have been made by me. I lift the receiver and the crackle and deep hum of the dial tone takes me back to teenage

, quick garbled ones you had to make before your money ran out. This phone box doesn’t take coins and doesn’t charge me, which I’m confused about. It turns out that there are some phone boxes that can’t take coins or cards, and offer free calls to UK landlines and mobiles.

I ring the only number I can remember without looking at my contacts list – my partner’s. He doesn’t pick up, because who, in this day and age, answers an unknown landline number? So I WhatsApp him to say it was me, ringing from a phone box! We’re both momentarily thrilled by the novelty, and the nostalgia.

Mobile phones are everywhere, Harris admits, but he points out that in this part of the country, the signal is sketchy. “We live next to perhaps the most beautiful part of Norfolk, the tranquil Glaven Valley with a pure chalk stream running through it. It attracts ramblers, walkers, the lot, and everyone knows that there’s a working kiosk.” Think if there was an emergency and the mobile network was down – something that may happen more frequently as we increasingly experience extreme weather, he says. “Wouldn’t it be awful if someone said: ‘If only they had kept that working kiosk’?”

It has been used in emergencies. “What you have to bear in mind is the few calls that have been made have been vital, they’ve probably saved someone’s life. Not that long ago, there was a snowstorm.” The mobile network was down and the call someone made from the phone box “was the only way that rescue came to save this driver whose car was completely covered in snow – it fell off the top of the hedgerows on to his car, and he was trapped”. And not far away is the main road, known locally as the Sharrington straight – a rare straight stretch of road where Norfolk’s most reckless drivers tend to speed up. Last year, says Harris, “we had two accidents in one day, both serious hospital cases. It’s an accident hotspot.”

He makes his case with justifiable, practical reasons why the phone box should be kept, but this isn’t the whole story, I realise, when we’re talking, out of the cold, at a nearby cafe.

“Wouldn’t you like to see a working K6 retained by BT, just for the sake of it?” asks Harris. He is a good talker. He distrusts human rights lawyers, and misses the days when people respected the police. But he’s not all traditionalist – he spent much of his career working in energy conservation. I think he likes purpose and order – he is dressed impeccably in pressed jeans and shirt, and pristine traditional overcoat – which could be why he isn’t keen on the way red phone boxes have been repurposed in other villages. Under BT’s Adopt a Kiosk scheme, phone boxes have become libraries, or home to defibrillators. Why can’t Sharrington’s enjoy a new life as something like that?

“It was not designed for that,” says Harris. “What it was designed for was communication. Why should it be changed into something else? It’s a telephone kiosk. It’s not some sort of library or whatever.”

Change it into something else, and it becomes a quirky relic of British history. Another dial tone dead. As a functional phone box, says Harris, “it would be alive, wouldn’t it? That’s why I feel empathy – I feel an empathy for a living thing.”

For Harris, it’s personal. There’s a comfort in continuity, and it’s about conserving what is worth conserving, leaving the world a better place, or at least not diminished. That includes a working, iconic red phone box in the village in which he has lived for so long. “It’s fighting for what is valuable, cherished.” The older he gets, he says, “there’s this thing about intimations of mortality. The nearer you get to the end, the more you want to see things live. I wouldn’t like to see it die. That’s the way to put it. That’s what I’m fighting for.”

The above photo comes from a Guardian article ‘Road to ruins: Peter Mitchell’s crumbling Leeds – in pictures’.

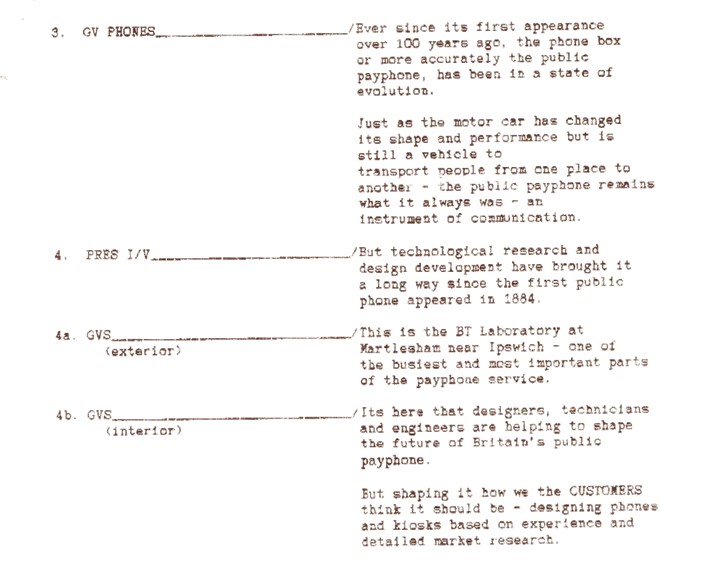

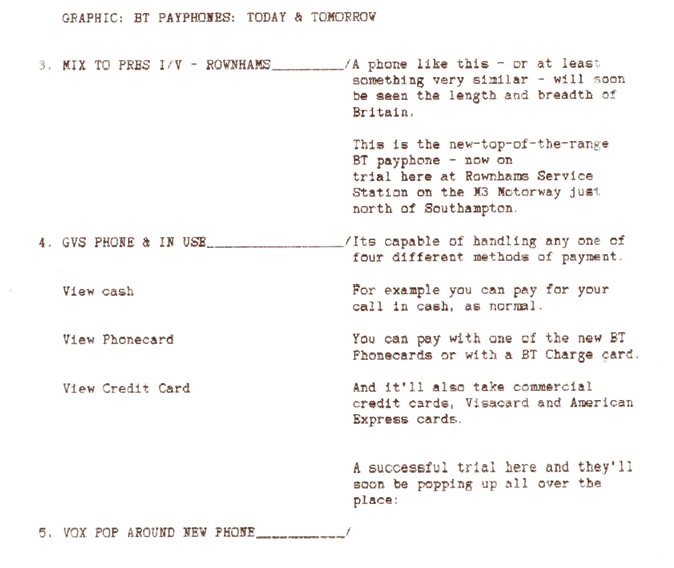

I came across an exciting find in the archives recently – a tv script from June 1992 entitled ‘BT Payphones’. Written by Crystal Images, likely for the tv show Tomorrow’s World, it includes scenes extolling the virtues of the payphone and selling it’s latest development, such as multiple payment methods. It seems that by the early 1990s our favourite red box was already seeen as ‘quaint and traditional – a unique symbol of Britain’s heritage’.

Here are a couple of screen shots:

Comments Off on Found in the archives

Posted in Comment

Tagged curiosity, heritage and history, television, UK

Just a memory

I enjoyed this FB post. It’s definately something I’ve aluded to – the idea that phone boxes remain useful as film and tv plot devices but are disappearing in the real world.

Comments Off on Just a memory

Posted in Comment

Tagged cinema, curiosity, heritage and history, television