Category Archives: Media

Art and the phone

“Amazing revelations’: the artist who asks passersby to bare all into an old-school telephone”

From The Guardian 28 May 2024

Joe Bloom has always admired the art of the phone conversation. “You see it in movies: it’s always this nostalgic and almost glamorous thing, holding a phone up to your ear and talking into this object,” he says. (Ironically, we’re talking over Zoom.) But many of us have cut phone calls out of our lives, losing touch with their otherworldly magic. While we’re perfectly content staring at screens and scrolling through endless content, speaking into the ether has become unnervingly unnatural. And even when we do take a call, it’s usually through earphones on the move rather than by actually sitting down and putting a phone to our ear.

For Bloom, this telephobia is part of a wider trend relating to our increasingly poor connections with each other. “There are a lot of barriers now stopping us from talking in certain ways to each other,” he says. As a young person, Bloom himself struggled with face-to-face interactions. “Growing up I found eye contact really difficult, and it made me struggle talking to someone.”

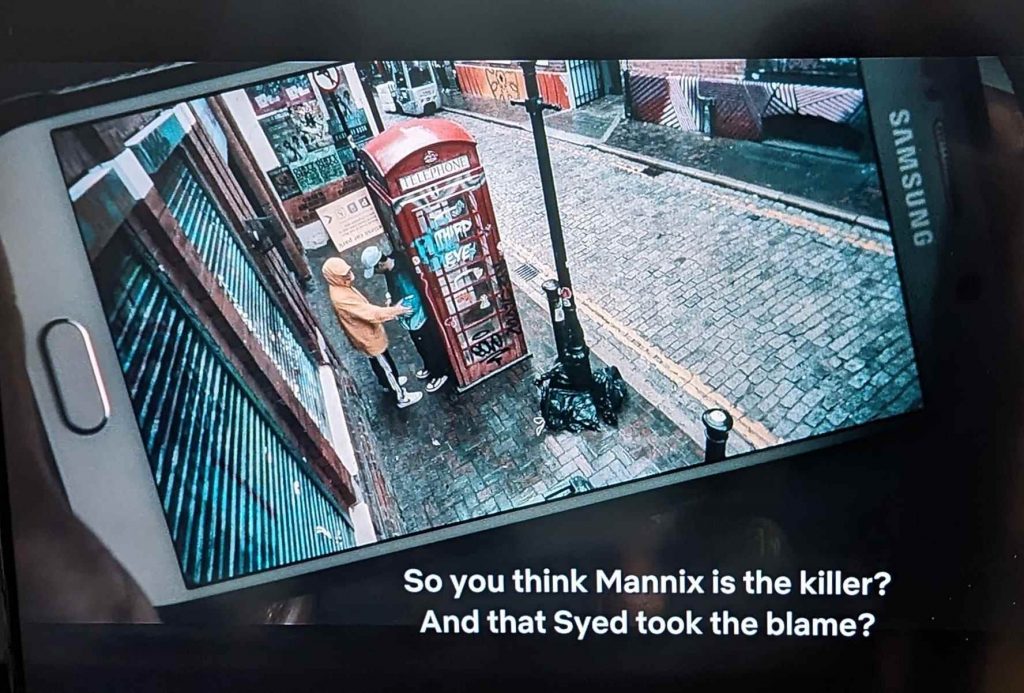

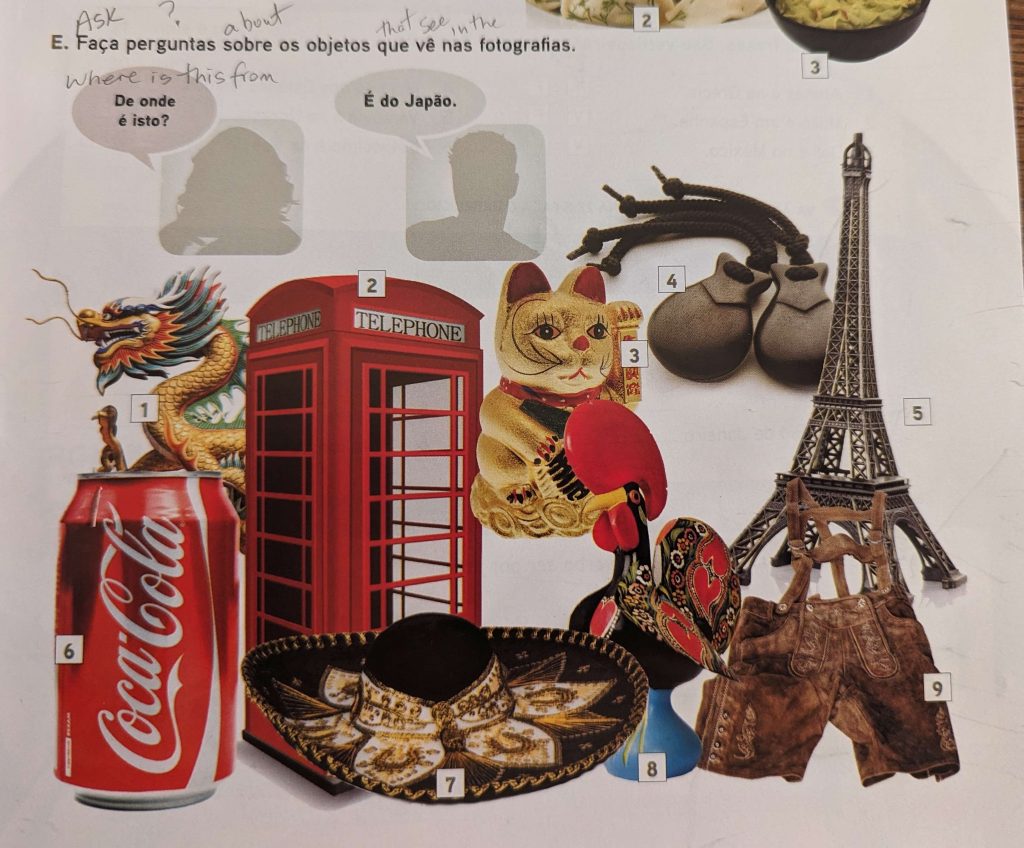

Now, though, Bloom talks and listens for the sake of art. His Instagram series A View from a Bridge invites strangers walking over London’s bridges to share their thoughts on life through an old-school red telephone, and pairs each recording with an introspective, carefully chosen piece of music. The project has been a hit; just three months since he posted the first video – which featured a man called Jason talking about the dangers of being overly patriotic – the page has amassed 232,000 followers.

In many ways, this social experiment seems to be in stark contrast to what Bloom is known for best: epic psychedelic oil paintings with vast colour palettes and vivid depictions of magical realist scenes, which have been showcased at the likes of Guts Gallery and Kristin Hjellegjerde Gallery in London. But he’s also a film-maker who has directed short dramas and documentaries. “I’ve always loved the projects that bridge a gap between film and art. I’m basically interested in storytelling,” he says.

A View from a Bridge stems from his love of early internet content, which was more about optimism than optimisation. “I remember being inspired years ago by Humans of New York on Facebook,” he says, talking fondly about the landmark portrait photography series. “What I really liked was that it had style but also substance.” But soon, he laments, our feeds were filled with ultra-processed content. “It went a bit nuts, and style and form were lost over just getting shit out there.”

This overflow of content includes lots of sketchy vox-pop videos. “Interviewing strangers is such a beautiful art form but it’s been made so tacky,” says Bloom. “You get some knobhead on the street running up to someone with a microphone asking them about their trauma. It feels awful. The AI-generated subtitles don’t even match up. It’s contrived and rushed. They just don’t care.”

From the outset, Bloom was drawn to the bridge as a setting for his project. “It’s an in-between place. You’re crossing over something, and that does something symbolic to your brain. It’s why there are so many phrases related to bridges,” he says. The final element was the series’ signature red telephone, inspired by one his mum owned.

On a February morning this year, Bloom placed it on Tower Bridge and (with the help of an assistant) invited passersby to pick it up and chat to him, while he recorded from 500 metres away. After some experimentation with the style, he landed on the series’ visual calling card: each video, shot lo-fi with a dated camera, begins with a closeup of the person talking, before Bloom gradually zooms out. In a way, it puts our own perspectives into perspective. “This individual person and their view of the world ultimately zooms out. The person becomes another cog in the system,” he explains.

The initial interactions were enlightening, but Bloom was anxious about sharing them. “I was terrified because the worst part of making art is having to share it,” he says. After sending them to friends and family, he worked up the courage to create the Instagram page and start posting. From the outset, he was always more interested in the people’s views than the video’s views. “I got a lot of joy just from my friends and family enjoying them,” he says.

Within weeks, millions more were coming across A View from a Bridge, after one of the videos – featuring a woman called Sue talking about working in HR – went viral. Her story involved a talented man at her company who was struggling to get promoted. Bosses in the workplace had been too scared to tell him the reason why – that his passion could sometimes spill over into anger. But when they eventually did explain this failing, he didn’t react badly, as they had expected, but understood immediately what he had to do to move forward. Sue says that, from that moment forward, she devoted herself to teaching managers the benefits of honesty in the workplace.

Since then, A View from a Bridge has featured topics of conversation ranging from the dangers of AI to running away to join the circus, and the real meaning of the term “ball-ache”. Thousands of people also join the conversations in the comments section, reacting, as expected, with a dizzying array of emotions and their own abridged stories.

Bloom thinks all this success is down to a simple fact: people love chatting. “I’ve learned that what people really want is to talk,” he says. It’s why he skews the interviews towards one-way conversations, often letting a silence hang in the air, to encourage people to speak their minds. Both he and us act as the listener on the other end. “This formula has allowed for some incredible revelations,” he says.

It’s also down to the power of the telephone itself. “It creates an openness for the person being interviewed. The action of holding the phone to your ear is powerful. It’s quite a calming thing,” he says. But he’s also encountered a barrier he didn’t expect: several young people who have wanted to get involved have been confused by the old-fashioned landline telephone. “It’s pretty funny. They don’t know what the hell this thing is,” he laughs.

Now on Patreon and increasingly taking up more of Bloom’s time, A View from a Bridge is set to reach even more people. Perhaps it will remind us not just of the art of the phone conversation but of the telephone itself, an engaging object that enables us all to open up – something many of us struggle with. “It’s quite a rare thing that people get the opportunity to do,” Bloom thinks. There is, it seems, life in the old dog and bone yet.

Comments Off on Art and the phone

Posted in Media

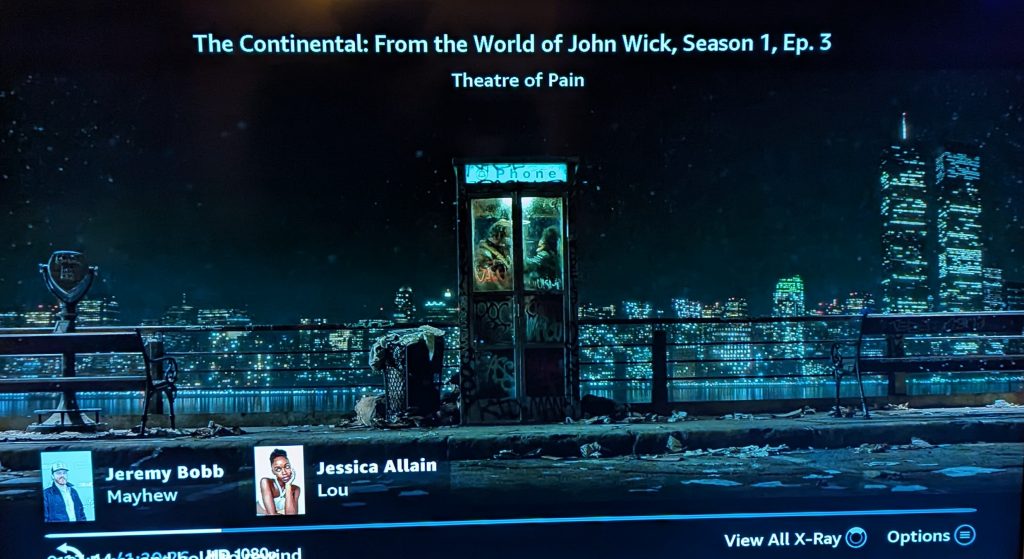

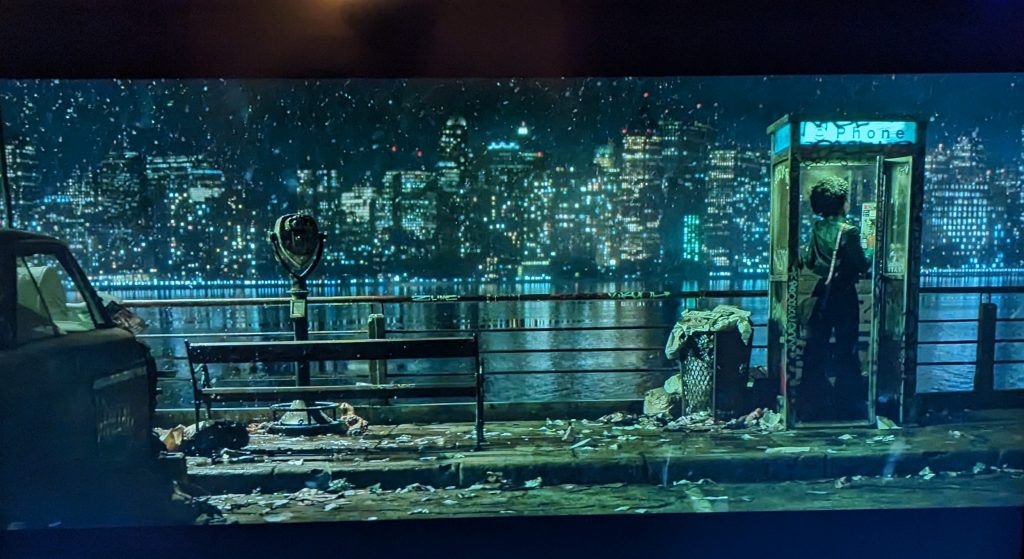

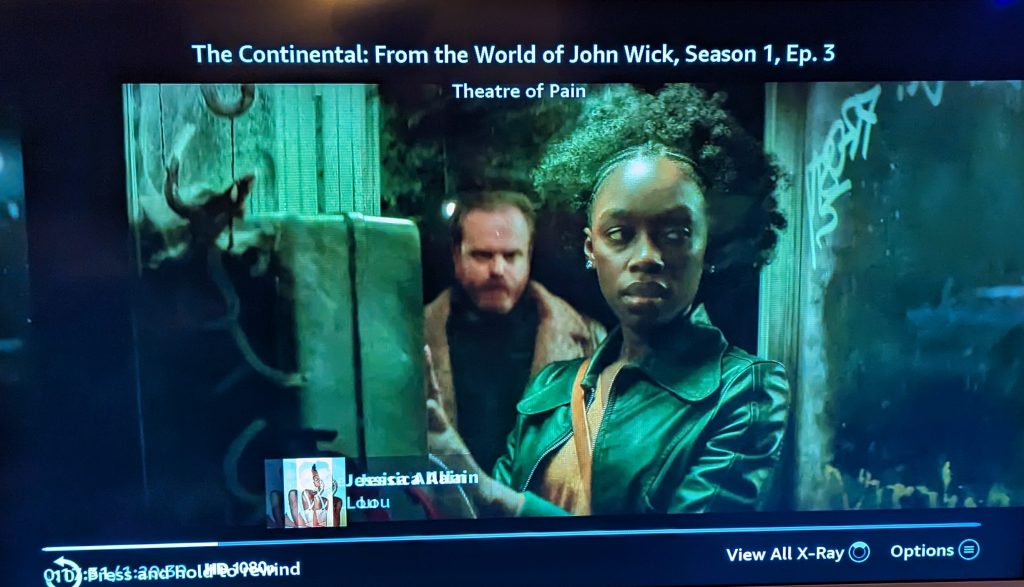

Watching the Box

Art

Why not?

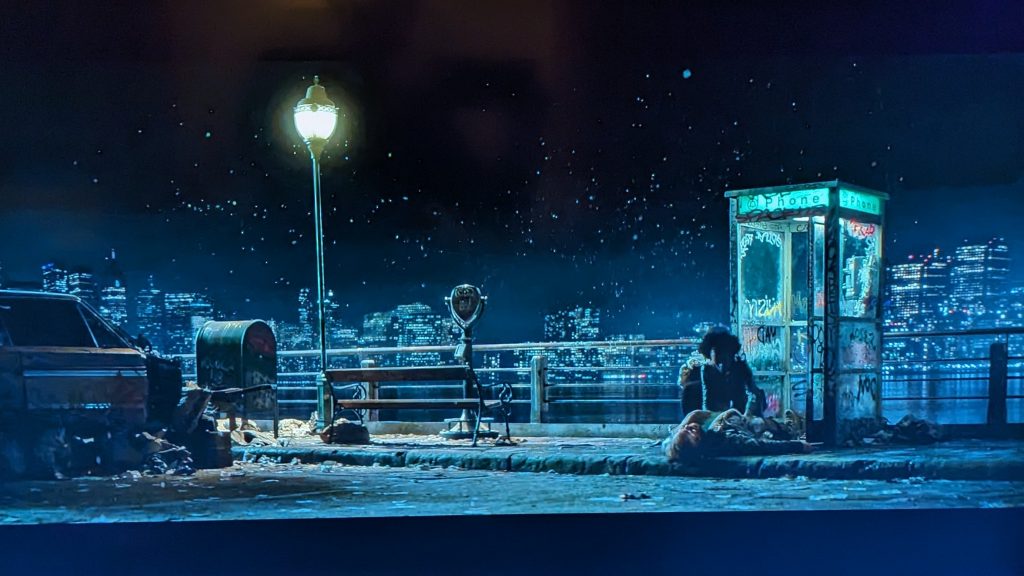

Mind palace

We’re currently watching The Undeclared War. The main character enters a mind palace when working on IT problems and the writers chose to use an iconic phone box in one representstion of this idea. Nice.